- expert system

-

a computer system that emulates the decision-making ability of a human expert.

In the late '70s, the Digital Equipment Corporation had a problem. Their newest instruction architecture, the VAX, was becoming incredibly popular.

But their catalogue of computer parts had become so long that they needed an expert just to figure out what components they’d need to put together to fit their requirements.

To illustrate this, on the right is a mainframe for a VAX 11/780. All the different hardware parts are stored and connected in these cabinets — and this is for just a single computer.

Considering that an expert was needed to fit together one of these computers, it isn’t all that surprising that DEC had difficulties training their salespeople to sell them. Hours would be wasted on consultations, and millions of dollars on replacement parts for misconfigured sales.

DEC hired an associate professor of Computer Science at Carnegie Mellon University called John McDermott. His task? Create a system that will automate this process.

Bashing Your Head at a Problem

A common problem-solving technique in computer science is that of brute force. Need to get through a door? Just bash it down.

McDermott didn’t really do anything too creative. In fact, he did something very simple — he asked the experts.

Of course, it wasn’t always a simple task, especially when experts disagreed over ideal configurations; but McDermott pressed through and eventually made the R1 Expert System.

The R1 was a monstrosity with over 2500 rules, but it worked — and it would eventually save DEC millions of dollars. It was the first commercially successful expert system.

Constructing an Expert System

Most AI problems are similar to most CS problems in that you know what input data should get you what output; for example, for any specific set of specifications (inputs), there’s some certain specific VAX configurations that’ll work for it (outputs).

What we’re looking to do is find a method, an algorithm, a schema to get from the inputs to the outputs. [1]

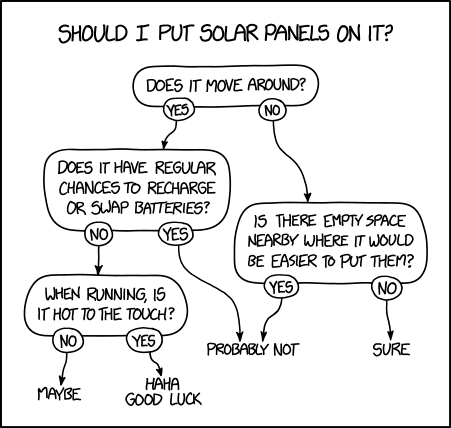

Alternatively, you can think of this as searching for some set of rules: if you have these configurations, then do this; otherwise, do that…

These rules can get as arbitrarily complicated as they need to be — sometimes they’d involve taking some of the inputs, doing calculations on them, and the using the result; or they can be as simple as a simple binary split.

Essentially, these rules come together to form an algorithm. And all algorithms can be represented by flowcharts.

And so designing an expert system, then, is just about writing out the flowchart.

In DEC’s — and McDermott’s — case, it turned out to be a twenty-five-hundred-rule monstrosity; that is, there’s at least twenty-five hundred different connections on the flowchart. The R1 was a complicated-as-heck algorithm.

But it wasn’t complicated — problem-wise — to build.

And now, you know how to make your own expert system.

The Expert System Bubble

The R1 was great. By 1986, it had processed eighty thousand orders — over twenty-seven a day — and saved DEC over twenty-five million dollars a year.

Its astounding success was widely reported, and in the 1980’s, there was a proliferation of expert systems. Academics wrote their PhD thesises on expert systems, and presented them at conferences overwhelmed by businessmen. CS professors quit their tenured positions, opening start-ups or becoming consultants.

And like all periods of economic boom fueled rapid advances in overly-hyped technology, the 1980’s developments in expert systems continued to grow without any problems!

Right?

Of course not.

The market for expert systems pretty much evaporated by the 90’s.

Why? What happened?

Well, let’s take a look back at DEC, their VAX system, and the R1.

What happens if DEC releases a new part? They’ll have to add some rules to the R1 so that it’ll account for it.

Or to put it another way, they need to manually review twenty-five hundred rules to check each and every one of them for tweaking or for additional exceptions.

Then they have to test it to see if it’ll give the right answers to inquiries after the tweaking was completed — that is, they’d have to check for bugs.

If each of these rules were binary classifiers — that is, each says "go this way or go that way" — then a one-rule tweak means there’s three different cases they need to retest[2].

A ten-rule tweak means there’s \(3^{10}\), or \(59049\) cases to retest. Manually.

And there’s some problems that simply can’t be approached in this way by a sane person.

Computer vision, for example, can’t be simply solved by human-written rules. Think about the last time you were looking for a specific building. How did you figure out that it was the right address? How did you figure out where the front doors were? Think about the the time before that, and the time before that. How many rules are you going to need?

We have an understanding of what numerical digits look like. A two looks like \(2\). But does it have to? Think about that one friend you have with horrendous handwriting. You can still recognize their twos. Think about how many people in the world have horrendous handwriting. You’d still be able to recognize many of their twos. Think about that one friend you have that has great handwriting. The way they write normally and the way they write extremely quickly is very different. You’d still recognize both types of their twos.

How many rules would you need?

It’s just not approachable.

And it’s no wonder that all-things expert-systems suddenly fell out of public sight.