Metrics

The easier question to answer is the latter. What does accuracy mean?

If we’re doing classification, then what we want should have something to do with the misclassfication rate. A 99% accuracy should imply that one in one-hundred videos are misclassified — either a propaganda video slipping through the cracks, or a harmless one being sent in for review.

But these two different types of misclassifications are distinct, and there are more than one type of error. And more than one type of success.

Real Positive |

Real Negative |

|

Classified Positive |

True Positive IS video sent for review |

False Positive normal video sent for review |

Classified Negative |

False Negative IS video released |

True Negative normal video released |

This sort of table to show these types of errors are called confusion matrices, as in "ways in which the AI algorithm can be confused."[1] And from here, you may begin to gather the problem with using "accuracy."

\(\text{Accuracy}=\frac{\text{TP} +\text{TN}}{\text{TP} +\text{FP} +\text{FN} +\text{TN}}\)

If a website received five million daily uploads, and only five hundred of them were for IS propaganda, it’s not difficult to achieve an accuracy even higher than 99%.

Just classify all videos negative.

\(\text{Accuracy}=\frac{\text{TP} + \text{TN}}{\text{TP} + \text{FP} + \text{FN} + \text{TN}}=\frac{4999500+0}{4999500+500+0+0}=99.99\%\)

liquid: true layout: lesson category: artificial-intelligence lesson: 2 --- = The Expert System

- expert system

-

a computer system that emulates the decision-making ability of a human expert.

You are a computer-part manufacturer. Your customers have many requests for their computers: they want them to be fast, to be able to hold plenty of memory in RAM; they might want both an SSD and an HDD; they might want a capable graphics card and adequate interfaces with external hardware. But each every component in your inventory is only compatible with certain models of motherboards, and given the hundreds of models of parts you have, you need experts to handle these requests, which you get many times a day. If only you could automate the process of coming up with compatible configurations…

Or maybe you run a busy hospital — the only hospital — in a large city. And despite the funds you receive, your hospital is always overcrowded; you can’t just buy the land the neighbouring skyscraper rests on, after all. You get many, many outpatients who only have a cold or a scratch and just need to get a prescription filled out, requiring a diagnosis by a doctor. And oftentimes, those with more serious ailments are misdiagnosed, considering how much time your limited doctors must work. If only you could automate the process of diagnosis and triage…

First developed in the 1970’s, the expert system was the first successful AI schema. Expert systems are built to emulate the decision-making of an expert, hence their name.

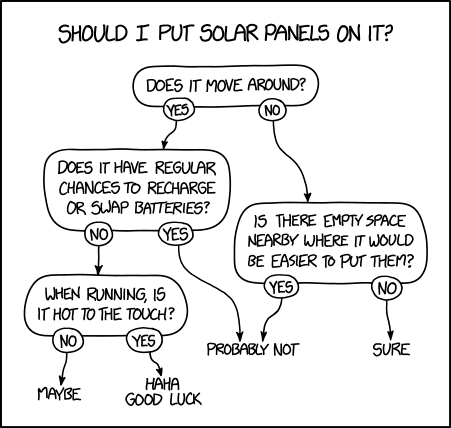

The most simple of these take the form of decision trees: if-then clauses that take some input — "I have these symptoms…" — and give you the output that an expert would come to: "You most likely have this affliction, but here are some other possible issues that can be narrowed down with these tests…"

Slightly more complicated ones can be represented with a flowchart.

The most simple of these take the form of decision trees: if-then clauses that take some input — "I have these symptoms…" — and give you the output that an expert would come to: "You most likely have this affliction, but here are some other possible issues that can be narrowed down with these tests…"

Slightly more complicated ones can be represented with a flowchart.

All expert systems can be boiled down to a deterministic algorithm: a set of instructions that, when given the same inputs, will come up with the same outputs. The only difference between an expert system and what are conventionally considered algorithms are that algorithms are expected to give perfect, objective answers to perfectly objective problems.

However, questions posed for artificial intelligences — and therefore expert systems — don’t have these precise metrics. As a result, whatever conclusions an expert system reaches are subject to the biases of the experts that were consulted during its construction.

This is a good thing in many ways: an expert system that creates ideal configurations of computer parts, once constructed, can save many man-hours per consultation, most of which would be about the same questions anyways. The actually interesting, unaccounted for problems can be sent to the actual experts.

Another pro for expert systems, as you’ll realize later on, is that whoever constructed the expert system can predict exactly what it’ll do, which makes it easier to fix any small bugs and errors or add small parts to it.

What is a big problem, however, is adding an entirely new feature or making a large update to the expert system; or, in more primitive systems that resemble flowcharts, adding a single new part. It’s not too difficult to imagine how a small change can simply spiral out of control.

Even more concerning is that certain problems are already impossible — practically speaking — to solve with an expert system. As just one example, there are numerous strategies available to Go players for any given position; just trying to classify the board into different positions is a feat to behold.

So what now? What new approach should we take?